Assassin's Creed 2 and 3: The Pinnacle of Series Writing

- By Jonathan

- Apr 15,2025

One of the most iconic moments in the entire Assassin’s Creed series unfolds at the beginning of Assassin’s Creed 3, as Haytham Kenway completes his quest to assemble a group of supposed assassins in the New World. At first glance, Haytham embodies the quintessential assassin traits: wielding a hidden blade, exuding the charisma of past hero Ezio Auditore, and performing heroic acts like freeing Native Americans from captivity and confronting British redcoats. However, the revelation comes when he utters the phrase, "May the Father of Understanding guide us," signaling to players that they've been unknowingly following the series' antagonists, the Templars.

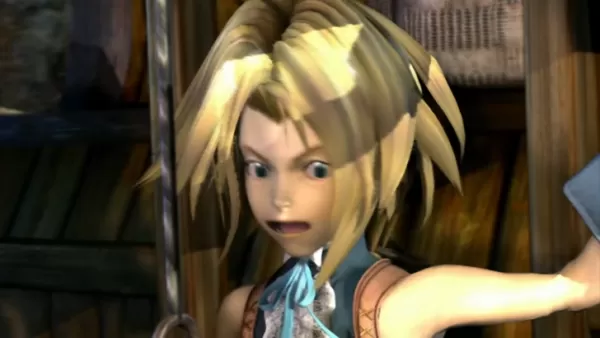

This twist not only shocks but also exemplifies the peak of Assassin’s Creed’s storytelling potential. The original game laid the groundwork with its innovative concept of tracking down and eliminating targets but lacked depth in character development for both protagonists and antagonists. Assassin’s Creed 2 improved upon this by introducing the beloved Ezio, yet still fell short in fleshing out his adversaries, notably Cesare Borgia in Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood. It wasn't until Assassin’s Creed 3, set amidst the American Revolution, that Ubisoft truly dedicated effort to developing both the hunter and the hunted. This approach created a seamless narrative flow, striking a balance between gameplay and story that has yet to be matched in subsequent titles.

While the modern RPG iterations of the series have garnered positive feedback, many in the gaming community believe that Assassin’s Creed is experiencing a decline. The reasons cited vary, from the fantastical elements like battling gods such as Anubis and Fenrir, to the introduction of diverse romance options, and the use of historical figures like Yasuke in Assassin’s Creed Shadows. However, I believe the true cause of this decline lies in the shift away from character-driven storytelling, now overshadowed by expansive sandbox environments.

Over time, Assassin’s Creed has integrated numerous RPG and live service elements, including dialogue trees, XP-based leveling systems, loot boxes, microtransactions, and gear customization. Yet, as the games have grown in scope, they've increasingly felt less substantial, not only in their repetitive side-missions but also in their core storytelling. For instance, while Assassin’s Creed Odyssey boasts more content than Assassin’s Creed 2, much of it feels less engaging and underdeveloped. The increased player choice, intended to enhance immersion, often results in scripts that feel less polished, as they must accommodate multiple scenarios. The tightly written, focused narratives of the action-adventure era allowed for more nuanced character development, which is diluted in the broader, player-driven structure of newer titles.

This shift has broken the immersive experience, making it clear that players are interacting with scripted characters rather than living within a historical narrative. In contrast, the Xbox 360/PS3 era of Assassin’s Creed delivered some of the finest writing in gaming, highlighted by Ezio’s passionate speech after defeating Savonarola and Haytham’s poignant final words to his son, Connor:

*"Don't think I have any intention of caressing your cheek and saying I was wrong. I will not weep and wonder what might have been. I'm sure you understand. Still, I'm proud of you in a way. You have shown great conviction. Strength. Courage. All noble qualities. I should have killed you long ago."*

The writing in later games has suffered in other ways as well. Where modern titles often simplify the moral landscape to Assassins being inherently good and Templars inherently evil, earlier games delved deeper into the gray areas between these factions. In Assassin’s Creed 3, each Templar's final words challenge Connor’s – and by extension, the player’s – beliefs. William Johnson suggests the Templars could have prevented the Native American genocide. Thomas Hickey criticizes the Assassins' idealism as unattainable, while Benjamin Church asserts that perspectives differ, with the British seeing themselves as victims. Haytham himself undermines Connor’s trust in George Washington, foreshadowing the eventual revelation that it was Washington, not Charles Lee, who ordered the burning of Connor’s village.

By the game's end, players are left with more questions than answers, enhancing the narrative’s depth and complexity. This approach to storytelling is what made the earlier Assassin’s Creed games stand out.

Reflecting on the series’ history, the track "Ezio’s Family" from Assassin’s Creed 2, composed by Jesper Kyd, became the series’ iconic theme due to its emotional resonance with players. It wasn’t just about the Renaissance setting but rather about Ezio’s personal journey through loss. While I appreciate the expansive worlds and advanced graphics of the current Assassin’s Creed titles, I yearn for the series to return to its roots with focused, character-centric stories. However, in today’s market, dominated by sprawling sandboxes and games with live service ambitions, such a return seems unlikely.

Latest News

more >-

-

- Elden Ring: Nightreign Preview by IGN

- Dec 31,2025

-

- Doom: Dark Ages Marks id's Biggest Launch Yet

- Dec 30,2025

-

- inZOI Bug Fix Stops Child Collisions

- Dec 30,2025

-

- MageTrain Releases Spellcasting Game for Mobile

- Dec 29,2025